Having a lot of data, in whatever form it might come – traditional paper records, microfilm or fiche, or electronic format– is presumably a good idea, otherwise, why bother having it? After all, we live in an information society where almost everything we do is dependent, in one way or another, on someone’s ability to access large quantities of data very quickly and accurately.

But the utility of that data –is dependent upon you actually being able to find it when it’s needed. That means you need a method of organization so it can easily be found. The larger the data set, the more this is true. You can shuffle through a stack of a couple of dozen sheets of paper to find what you need without too much difficulty. Make it a hundred and it’s a lot tougher. A couple of thousand, and it’s a very difficult, time-consuming, and error-prone task. A million – not a chance. And the reality is that a commercial records system, even a small one, is going to resemble those million pages, whether it’s electronic or paper, or a mix of record types.

The implications of that are straightforward but profound– you need a method of organization, otherwise, you’ll never find things. Most of your information will be effectively lost to you. If you have an organizational method, the utility of your information directly corresponds to the quality of your method. Indices, metadata indexing, and data structures are crucial to establishing order in your data set.

Is Your Metadata a Signpost, or a Map?

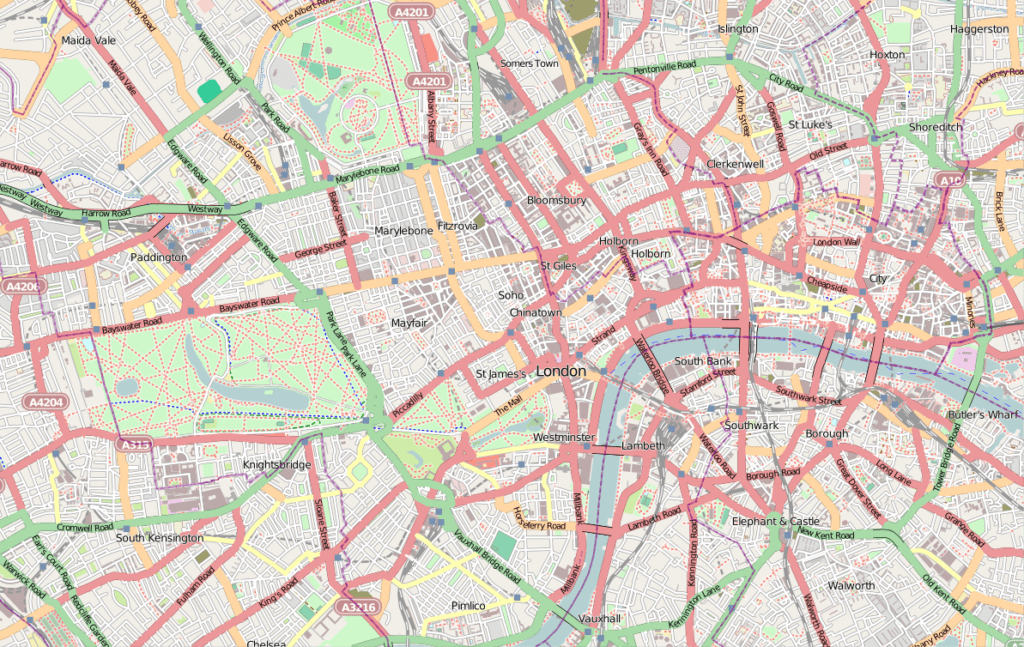

If you’ve ever driven a car in a very big, very old city – London, for example – you know it’s very difficult, to say the least. The streets aren’t organized according to any scheme, they’re all just a jumble that has accrued over many years. However, the streets are still possible to navigate because they have a metadata tag in the form of a name. So, those of us who have not memorized the entire map (as London cab drivers do) can sort of navigate around with a map or detailed directions.

Absent street names would make navigation impossible. However, because this metadata in the form of street names is in no way organized, its value is limited. That’s why cab drivers memorize the whole lot.

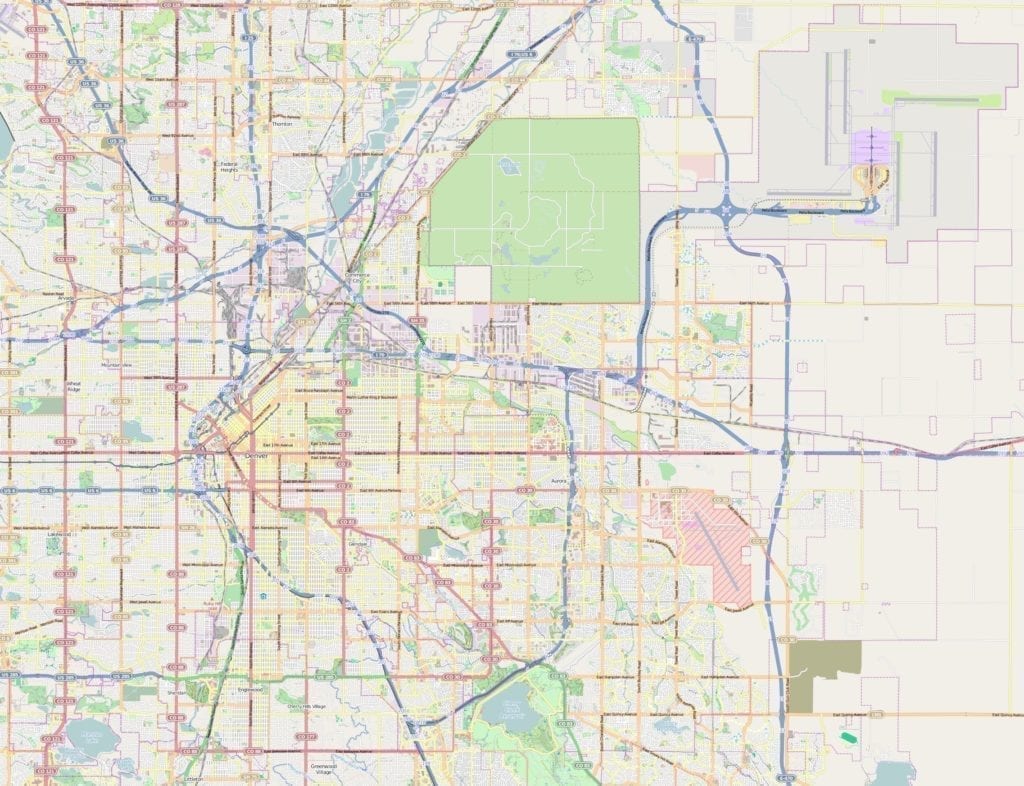

Compare that to Denver, Colorado. The entire city is laid out on a numbered grid. That organizational fact alone simplifies navigation. There’s a street corner that is the zero point – zero east-west, zero north-south. And in addition to a name, every street has a number – 100, 200, and so on.

So, if I tell you that Pennsylvania Avenue is 500 East, you easily figure out where that is. If I tell you to go to 4340 South Pennsylvania, you know that’s 5 blocks east and 43 blocks south. The city also named blocks of streets as consecutively numbered avenues after trees, historical figures, and so on. Once you know the system and the naming conventions, Denver is very easy to get around in. That’s because the entire city has a consistent metadata method of organization, and the objects in it are laid out in an ordered systematic way.

Organizational techniques for managing data sets aren’t too far removed from this sort of comparison. Without some sort of information about what’s in the data set, you’re left to rummage around randomly, like driving through London without a map and no street signs. Metadata is necessary, and the more consistency and order your metadata indexing has, the more effective it becomes for you.

Beyond Storage – A Comprehensive Information Management Checklist

Organizations of all kinds and sizes are finding themselves faced with an array of information management challenges. Some of these challenges, like the transformation of information technologies and the growth of data sets, have remained relatively unchanged for years.

Filing Systems – Metadata for Physical Records

There’s an assortment of filing systems for physical records in common use – numeric, alpha-numeric, terminal digit, and so on, but they all achieve some of the same important goals:

- Files have systematic, predictable metadata tags attached to them

- Files are stored in systematic, predictable locations

- Files on the same or similar topics are either physically grouped (by location) or logically grouped (by the coding on the file labels)

Special-purpose systems like terminal-digit systems may not seem logical to the uninitiated, but this method of organization does accomplish the above. If you’ve ever dealt with a physical filing system that has imprecise labeling and filing, you appreciate how important that method of organization and its consistent application are.

Applying Organizational Techniques to Metadata for Electronic Systems

The same logic applies equally to electronic systems. Your computer’s file folder is simply a digital version of a paper filing system. You may think that a systematic data structure is unnecessary, advocating for freeform metadata tags as the sole tool. However, this perspective fades fast because relying solely on freeform metadata becomes insufficient as the collection’s data objects increase. To illustrate, think of a paper filing system with a thousand cabinets. If you randomly fill them with unlabeled file folders, you end up with a chaotic and useless system.

Randomly label the folders and it’s a bit better… but not much. You’d still have a difficult time finding a particular folder. It’s only when you systematically label and file the folders that the method of organization really begins to function. With electronic systems, data objects aren’t necessarily contiguous physically, but the metadata scheme ties them together logically.

Metadata Schema and Index: How Different are They?

You may hear someone say “We don’t use indices, we have a metadata schema.” Is metadata somehow different than an index?

The metadata schema defines the attributes and characteristics of the data, while the index provides a streamlined way to access that data quickly. A robust data system often utilizes both a well-structured metadata schema for detailed information and an index for swift and efficient retrieval. Consider this simple index example:

- Accounting

- Accounts payable

- Accounts receivable

- Human resources

- Applications and resumes

- Personnel files

Every data object in this system will have at least two metadata tags associated with it, for example, ‘human resources’ and ‘personnel files.’ The first one places the object in a particular group of data objects, and the second one puts it in a smaller subgroup. Each personnel file would then have at least one additional metadata tag in the form of a name or employee ID number to permit the identification of a particular file. With both an index and metadata schema, documents can be found quickly and easily.

Empowering a Better Search Experience with Metadata and Index Structure

The beauty of a well-designed electronic system is that this logical hierarchy can be paired with all sorts of additional metadata – date and time stamps, keywords, author, the list is virtually endless. Then, these metadata fields can be paired, sorted, filtered, and displayed in a multitude of ways that can’t be done with a physical filing system, allowing you to search in powerful ways.

To put that power to use, your scheme must be systematic, ordered, and consistently applied. If you don’t consistently label documents as invoices or don’t consistently put Joe’s name to them, then it won’t work effectively.

So, what’s the best way to lay out an index? Well, there isn’t one. Consider this simple index for business tax forms. Which structure is better: by form number or by year?

Structured by form number

|

Structured by year

|

The superiority of an organizational method depends on the nature of searches within the system. Your goal in building the index is to provide the shortest search path possible to anyone searching the system. You can’t optimize the index for every kind of search, so you optimize it for the most common.

If you mostly look for all tax forms for a single year, the second scheme makes more sense. If you’re mostly dealing with a single kind of form over multiple years, the first makes more sense. As a result, an organizational method optimized for day-to-day accounting work is likely to look very different than one optimized for responding to audits or lawsuits.

When creating an index and other metadata tags, you must first get a sense of who is doing the searching, how they do their work, and how they search for things. The same is true for the index terms themselves – they must be meaningful to your users, otherwise they’ll be hunting around randomly. It’s also worth noting that in a good electronic system, you may be able to reorder your index and display it in other ways as well – reordered, combined with other metadata fields, or flattened out, for example. So, in our accounting example, you could have both layouts available as needed.

Success is All in the Planning

Thoughtfulness and care in crafting your metadata terms and structure, along with a high degree of consistency in their application, are crucial keys to success. The challenge is always in building the intellectual capital – index, data structure, metadata set – that will drive the system. Build it well, and it will be effective in any environment because it contains the key information and relationships that allow effective searching.

To learn more about metadata and how to break the pattern of repeatedly searching for documents, read Moving Beyond Groundhog Day: Practical Solutions for Enhanced Document Management. This quick read provides a solution for applying metadata to your documents when resources are minimal.